|

In healthy individuals after eating a mixed meal, it usually takes about 4-5 hours for that meal to completely empty the stomach and 5-6 hours for that meal to empty the small intestine. This all can vary depending on what you eat and how well your gut muscles are working. Eventually, the remaining unabsorbed food matter (like fiber) and water, move through the ileocecal valve, the doorway from the small intestine to the large intestine. As the unabsorbed matter passes through the ileocecal valve, the large intestine monitors how much undigested material there is. If there are increasing amounts of undigested food, especially fats, it signals to the small intestine to S L O W D O W N. This is called the ileal break and is necessary to help maximize our absorption of nutrients. This mechanism also reduces our appetite. This is why when individuals struggle with diarrhea, they often do not have much appetite. Once the unabsorbed liquid food matter passes through into the large intestine a few things happen:

On average in healthy folks it takes about 30-40 hours for the mass to travel the entire 1.5 meters of the large intestine, going up along your right side (called the ascending colon), across your upper abdomen (called the transverse colon) and back down your left side (called the descending colon). In individuals struggling with idiopathic constipation, their colonic transit time can be greater than 100 hours! When colonic transit time is slowed and stool is stagnant in the colon, it allows chemicals, toxins, and hormones originally bound for elimination, to be reabsorbed into circulation. This can increase your risk of hormonal imbalance and impaired detoxification due to increased stress on the liver and kidneys. Also, slowed transit time can contribute to diverticulosis and colon cancer, as well as the overgrowth of bacteria and fungus in both the small and large intestines. Furthermore, slowed motility usually presents along with hard to pass stools and straining, leading to uncomfortable hemorrhoids. The total amount of time for a meal to be digested and absorbed and the remainder excreted as a bowel movement is called your gastrointestinal transit time (GTT). If your transit time is <12 hours you are likely struggling with nutrient malabsorption, if your transit time is >48 hours then you are likely struggling with constipation. If it takes more than 72 hours for food to travel from mouth to toilet, there is significant backup. I find that around 24 hours is usually the sweet spot for most—what you ate yesterday, leaves you today! Are you curious what your stool transit time is? Generally, if you eat a higher fiber diet, stool transit time should be faster than if you eat a low fiber diet. However, if you eat a high fiber diet and still struggle with constipation something else is going on. This is the perfect time to work with a gut health dietitian for guidance. TESTING YOUR STOOL TRANSIT TIME Although not the gold standard, testing stool transit time at home can give you a rough estimate on your personal window. Sesame seeds remain undigested and pass through the gut intact. White hulled sesame seeds are more easily seen than dark sesame seeds. Alternatively, eat a steamed red beet. THE SESAME SEED (or red beet) CHALLENGE

References: Gastrointestinal Tract: How Long Does it Take? http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/digestion/basics/transit.html Ileal Brake: neuropeptidergic control of intestinal transit. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16968603/ Physiology, Large Intestine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507857/ Measuring colonic transit time in chronic idiopathic constipation. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

0 Comments

You WANT a stomach NINJA, not a stomach COUCH POTATO. Once food is swallowed as a bolus, it enters the stomach and stretches the stomach lining, activating stretch receptors and stimulating the parietal cells to make more stomach acid. In fact, the gastric phase is responsible for 60% of stomach acid production whereas the cephalic phase is responsible for about 30%. Continuous activation of the enteric nervous system (which can be influenced by the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems) also stimulates the release of gastrin causing an increase in strong and vigorous muscle contractions, and pepsinogen from chief cells. Pepsinogen, in the presence of adequate amounts of stomach acid, is then activated to pepsin, a protein digesting enzyme. As your stomach churns your food and mixes it with stomach acid and digestive juices, it also starts the process of B12 digestion and absorption. Stomach acid separates B12 from animal proteins so that B12 can bind to another protein called intrinsic factor which is only produced in the stomach. This process is essential in order to absorb B12 from our food. Plus, it can also kill potentially harmful bacteria, viruses, and parasites, coming in through your food. So now your stomach is not just a powerful blender…it is a mean blender NINJA. After foods have been properly broken down, the stomach gradually releases the stomach contents (now called chyme) into the upper small intestine. However, if you have a higher fat or higher fiber meal, stomach emptying is slowed, and can contribute to longer feelings of fullness, than if you had a low fat processed meal, like cereal. Common symptoms of low stomach acid:

I see many of the aforementioned symptoms in my practice all the time. There are many reason why someone might have low stomach acid, and sometimes there is more than one variable involved. Below I have highlighted those that I see most often.

Okay, now you likely want to know, “Do I have low stomach acid?” If you experience chronic digestive issues and any of the symptoms mentioned above, then the answer is likely yes. Once you address your stomach acid production, then you can help improve many things downstream on the river of gut health. Therefore, it is essential to address this first! How do you Test for Low Stomach Acid? The gold standard is a Heidelberg Stomach Acid Test and can get expensive, averaging around $350. Unfortunately, many GI doctors do not run this test, even when patients ask for it. If you want an alternative to this, then check out the simple at home test below to see if you struggle with low stomach acid. Baking Soda Challenge Although this test is not supported by any studies, it can be a simple and cheap way to check your stomach acid production. All you need is a fresh container of baking soda and water.

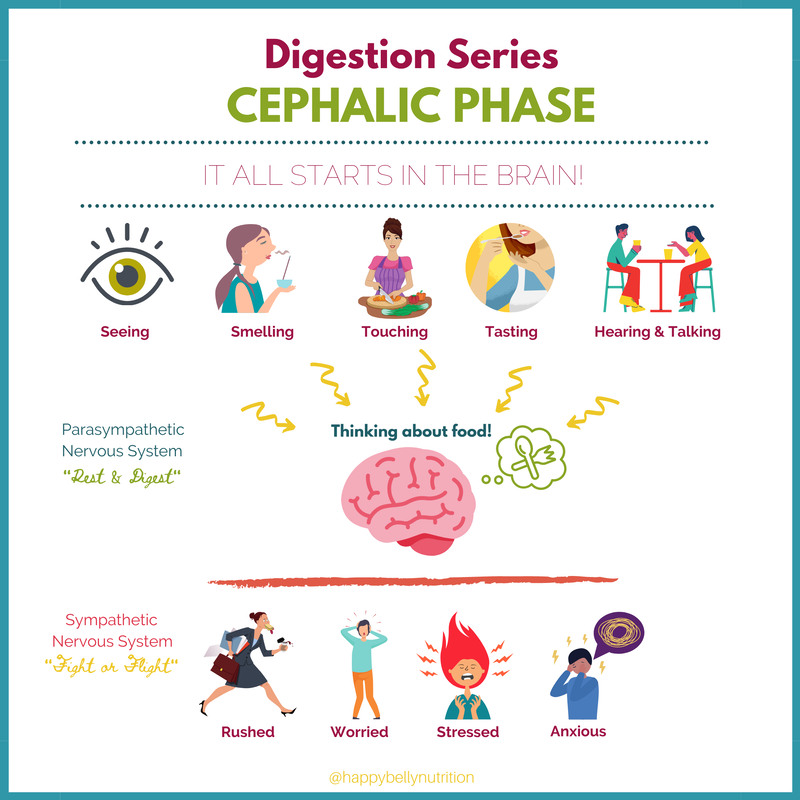

If your results suggest LOW stomach acid, then it’s time to figure out WHY and work with a gut expert. If you want my help and guidance, then make your discovery call today! References: http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/digestion/stomach/onemeal.html https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499926/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15184707/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3460328/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20581234/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5076771/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3144339/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1494327/ https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/proceedings-of-the-nutrition-society/article/ageing-and-the-gut/A85D096755F5F7652C262495ABF302A0 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8612992/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6354172/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2690329/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2858363/ Using our five senses (seeing, smelling, hearing, touching, and tasting) we trigger the start of digestion via the cephalic phase. Our senses stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system (rest & digest) to communicate via the vagus nerve to our enteric nervous system which governs our gastrointestinal tract. This results in the release of a variety of different neurotransmitters, chemicals, and hormones that stimulate the parietal cells to secrete stomach acid and to stimulate the stomach to start churning slowly. It is as if we placed a skillet on the burner and turned it on. Overall the cephalic phase contributes to about 30-50% of our total stomach acid production! And did you know that simply talking about food can stimulate this same response? A research study from 1986 found that simply talking about appetizing food for 30 minutes without seeing it, smelling it, or tasting it, increased stomach acid secretion by 66% whereas seeing and smelling food only stimulated stomach acid secretion by 23-46%. Other topics of conversion did not elicit any stomach acid production. This goes to show, that what we are thinking directly impacts our digestion more than what we are seeing or smelling, and that seeing and smelling really just stimulate stomach acid production because we start THINKING more about food. Now let me put this into perspective. What is different between these two scenarios? Scenario #1: It’s breakfast time! You go to the fridge and quickly pull out a mason jar of chia berry overnight oats even though you really don't have appetite for it. Instead of sitting down you eat a few bites, get dressed, eat another few bites, put on your shoes, and then gobble down the rest. You quickly grab your bag and head to the car to go to work. Scenario #2: It’s breakfast time! You look into the fridge, think “hmmm, what sounds good? Oh yea, a fried egg on avocado toast sounds delicious!” You heat up the skillet, add a little dollop of butter and hear it sizzle, you crack open the egg on the skillet and hear “tsishhhh” as the egg hits the heated pan. You place a piece of toast in the toaster and wait until your egg and toast are done. As you wait, your appetite builds and builds, and you can’t wait to enjoy the ooey, gooey delicious mess that awaits you. Your toast pops up, you top it with creamy avocado, your crispy, fried egg, and sit down at the table to enjoy this fork and knife breakfast meal. Although both meals are healthy choices, scenario two allows for optimal digestion because not only is more time spent thinking about food, but the preparation of the food allows all of the senses to be active. If scenario one is your go-to relationship with food, then it is no surprise why you may feel overly full and bloated. When eating in a rushed, hurried, and stressful state of mind, we inhibit the parasympathetic nervous system, and therefore inhibit the stimulation of the vagus nerve and the enteric nervous system. Our energy is shunted away from “rest and digest” and rather focused towards “fight or flight” and our sympathetic nervous system. Since the cephalic phase primes the gut for the meal to come, we cannot overlook how powerful it is to simply, slow down when it comes to food. We must allow time in our busy days to appreciate and to look forward to the foods and meals we consume. The saying “eat to live” easily distracts us away from the importance of acknowledging our food as something more than just simply fuel but as something that should be enjoyed. Seeing food through the eyes of a “foodie” can be one very helpful step that can enhance your gut health. Some Tips from your Gut Health Expert:

Are there any changes you are willing to make to your eating routine to enhance your cephalic phase? Share with me below! References: 1) Feher. Quantitative Human Physiology (2nd Edition). The Stomach. 2017. 2) https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/0016-5085(86)90943-1/fulltex Did you know that taste can influence our digestion? We have five tastes: sweet, salty, bitter, sour, and savory (umami). These taste receptors are located not only on the tongue but also throughout the entire body including (but not limited to) the entire GI tract, as well as the immune system, heart and even the brain. Bitter plant compounds, are most often used to support digestion. In fact, they have been used for centuries to relieve common gut symptoms such as indigestion, bloating, and feeling full fast. Interestingly, research has found that we have 25 different bitter receptors each stimulated by different bitter compounds. These receptors are also found in the stomach, and once stimulated, support stomach acid production. Therefore, bitter greens (such as radicchio, chicory, endive, kale, arugula), citrus (especially citrus peels), rhubarb, and caffeinated beverages like coffee, green and black tea, can all support healthy stomach acid production. Beer and wine can also stimulate stomach acid production due to their alcohol content and as well as their bitter compounds. However, keep in mind that alcohol itself can contribute to irritating GI symptoms. Why is this important? For good gut health, we need proper stomach acid secretion. Stomach acid is essential to help us break down and digest our food (especially protein) and acts as a barrier for incoming bacteria either via our food or oral cavity. Stomach acid also triggers the release of bile from the gallbladder and triggers the release of digestive enzymes from the pancreas. Therefore, stomach acid is essential for optimal digestion. Furthermore, bitter compounds are also found in the duodenum (first part of the small intestine), and directly stimulate the release of cholecystokinin (CCK). CCK is a hormone which stimulates the release of bile from the gallbladder and the release of digestive enzymes from the pancreas. Bile is essential for the absorption of fats and fat soluble vitamins A, E, D, K and digestive enzymes are essential to break down all of our food into small enough particles for easy absorption. If you are motivated to increase your bitter foods for enhanced digestion check out the ideas below. There are many options besides eating an arugula salad that can help boost your daily bitter intake.

Clinically, besides bitter foods, bitter herbs found in tinctures can be helpful for more immediate relief. I suggest taking the bitters directly into the mouth and then swishing the bitters around for a few seconds before swallowing. I often recommend the following: Iberogast: 20 drops with meals or 60 drops before bed Urban Moonshine Original Bitters: 1 dropperful before meals Urban Moonshine Calm Tummy Bitters (safe for pregnant mamas) Herb Pharm Better Bitters: 1 dropperful before meals Swedish Bitters: 1 tsp before meals References:

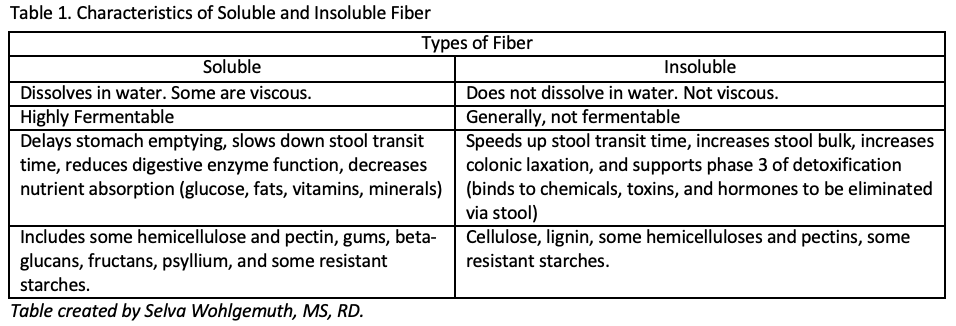

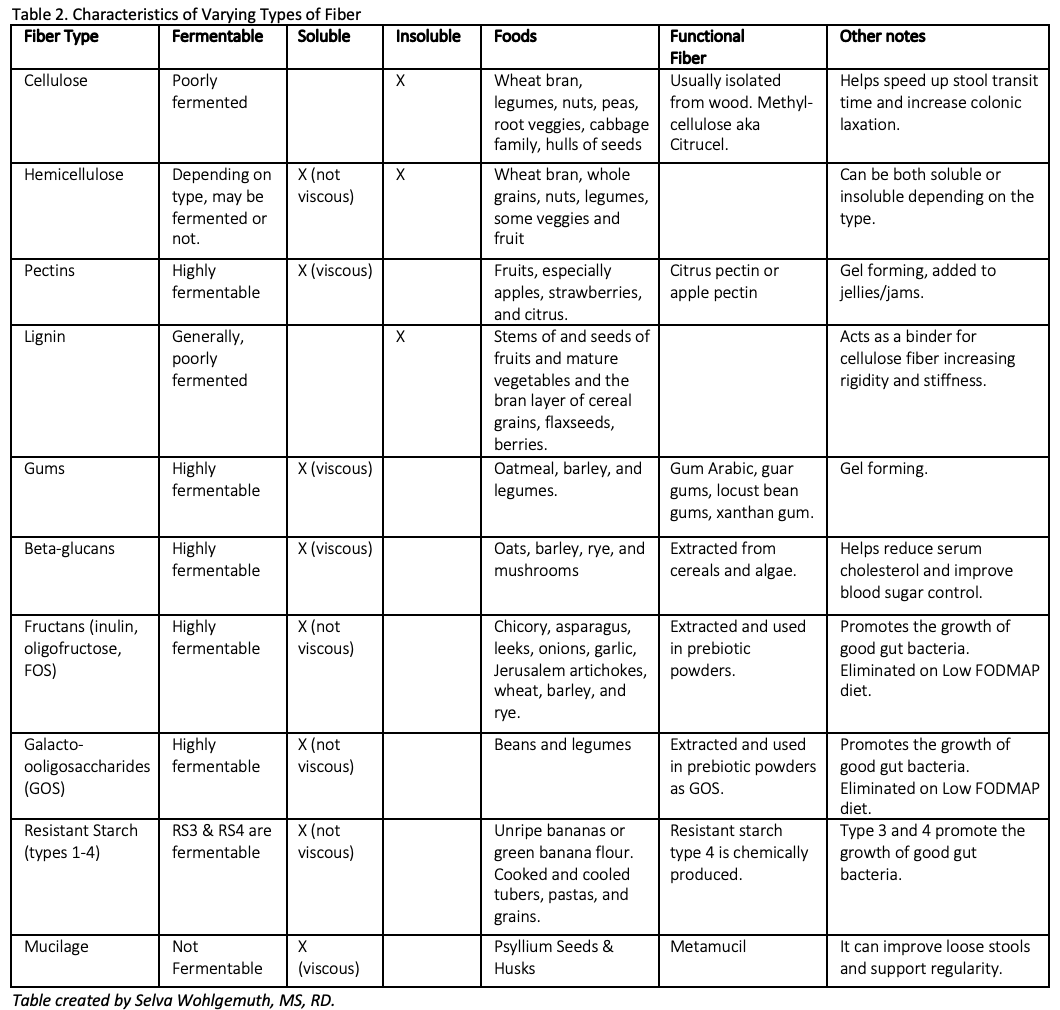

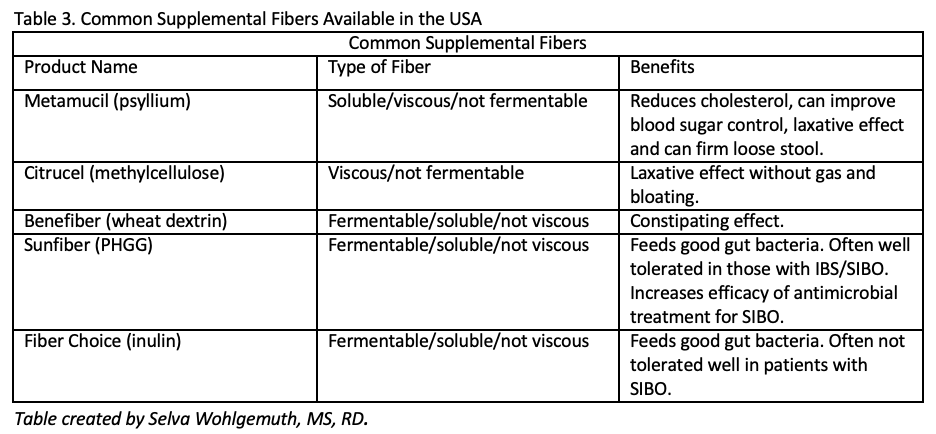

Gut chemosensing; implications for disease pathogenesis.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5054811/ Characterization of Bitter Compounds via Modulation of Proton Secretion in Human Gastric Parietal Cells in Culture .https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28525714/ Caffeine induces gastric acid secretion via bitter taste signaling in gastric parietal cells. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5544304/ Alcohol and gastric acid secretion in humans. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1374273/pdf/gut00557-0145.pdf Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal system. https://flavourjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2044-7248-4-14 First of all I want to start off with a fun fact, not all fiber is the same, nor does it work the same in the gut. Fiber can be complicated. However, today I am going to try and break it down for you. Dietary fiber refers to plant carbohydrates that we humans cannot digest because we lack the digestive enzymes to break them down. These fibers include cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, lignin, gums, beta-glucans, fructans, galactooligosaccharides, and resistant starches. Each part of the plant (stem, root, leaf, etc) and its age all are factor into what fibers are present upon consumption. See Table 2 below for more info on each type of dietary fiber. SOLUBLE VS INSOLUBLE There are two main categories generally used to categorize dietary fiber – soluble fiber and insoluble fiber. We need both for optimal gut health. Soluble fiber dissolves in water and often has a high water holding capacity, creating a gel like (viscous) substance. This gel like substance can firm up and soften stool, and therefore can help reduce severity of diarrhea while also softening hard stools. However, it also slows down the speed of which food/fibers travels through the gut and can reduce the absorption of nutrients. Soluble fiber is also highly fermentable by gut bacteria. Insoluble fiber on the other hand, does not dissolve in water, does not create a viscous gel, and generally is poorly fermented. Instead it acts like straw, bulking up the stool, supporting movement out, and cleaning the gut along the way helping to slough off dead cells. Soluble fiber is more gentle and can be better tolerated if someone has gastritis or intestinal inflammation, while insoluble fiber is more rough and can be irritating to inflamed tissue. FERMENTABILITY Although both soluble and insoluble fibers can be degraded by colonic bacteria, soluble fibers are fermented at a much higher degree. Fermentation of fibers usually happens in the first part of the colon, where bacteria breakdown the fibers that we cannot digest and produce hydrogen gas as a byproduct. Therefore, fermentable fibers are known as prebiotics, or food for good gut bacteria. The most fermentable dietary fibers include fructans, galactooligosaccharides (GOS), pectin, gums, beta-glucans, and resistant starch type 3. Fermentation produces energy for the beneficial microbes and provides humans with short chain fatty acids (mostly acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid). Short chain fatty acids provide humans with a lot of different health benefits including 1) they stimulate mucous production in the colon which aids in elimination and encourages the growth of akkermansia (a keystone species of gut health), 2) they decrease the pH of the colon which prevents the growth of pathogenic bacteria, 3) they provide fuel for the colon cells, 4) they enhance immune function, 5) they help prevent colon cancer, and 6) they can inhibit cholesterol synthesis in the liver. Each unique bacteria preferentially ferments different fibers and therefore produces different types of SCFAs. Therefore, in order to reap these benefits, we need to eat a wide variety of plant fibers. VISCOSITY Viscosity, or gelling power, varies amongst fiber types. Some soluble fibers are viscous and all insoluble fibers are not. The higher the viscosity, the greater the gelling power, and the higher the water holding ability. Viscous fiber SLOWS stomach emptying and stool transit time. Therefore, it can help increase satiety and provide relief when struggling with loose stools. However, if soluble fiber is also fermentable (most soluble fiber), then it does not provide constipation relief. Since fiber is fermented in the first part of the colon, it loses its water holding capacity, and may therefore contribute more towards constipation (especially in supplemental forms like wheat dextrin). However, if the soluble fiber is highly viscous and NOT fermentable, like psyllium, it can increase stool water content throughout the entire length of the colon, providing relief for both loose stools and constipation. Viscous fiber can also reduce absorption of nutrients by binding to them and reducing digestive enzyme function. Therefore, highly viscous soluble fiber is found to be helpful at reducing cholesterol and blood sugar levels. However, if someone is already struggling with malnutrition or nutrient deficiencies, too much soluble fiber may further impair nutrient absorption. BUT, if stools are loose, slowing them down with soluble fiber, will increase the time allowed for nutrient absorption, thereby increasing the ability to absorb nutrients from the diet. Soluble and viscous fibers include pectins (apples, citrus, berries), gums (oats, barley, legumes), beta-glucans (oats, barley, rye, and mushrooms), and psyllium. They are all highly fermentable, except psyllium. The more processed (heat & pressure), the less they retain their viscosity. Therefore, muesli eaten cold with yogurt is going to retain more of its viscosity than Cheerios. Another example would be a functional fiber, partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG). This functional fiber has been chemically altered to remove the viscosity of raw guar gum. Therefore it no longer has gel forming properties but remains soluble and fermentable. NON-FERMENTABLE, NON-VISCOUS INSOLUBLE FIBERS Non-fermentable, non-viscous, insoluble fibers not only provide benefit by increasing fecal bulk and speeding up transit time, they also support detoxification. Since insoluble fibers help support regularity, they are essential for eliminating environmental toxins, chemicals, and excess hormones. If stool stays stagnant in the colon for too long, we can reabsorb these chemicals, toxins, and hormones, leading to increased inflammation and hormonal imbalances, and eventually leaving us feeling crummy, fatigued, and inflamed. Can anyone relate? If you don't have your daily poo, you don't feel like you?? Insoluble fibers also help increase stool bulk which aids in the laxation of the colon and reduces straining. Interestingly, research shows that the larger the fiber particle, the more potent the laxative effect. Therefore coarse wheat bran, which is high in insoluble fiber, is a much more effective laxative than fine wheat bran. YOUR LIKELY NOT EATING ENOUGH FIBER Unfortunately, 95% of Americans are not getting enough fiber. That means only 5% of Americans are actually meeting the daily recommended intake of 26-38g per day for women and men respectively. And although you may think you are getting enough fiber, research shows that only 1 in 20 actually do! With the rise of grain-free, bean/legume free, and gluten free diets, daily fiber intake can take a significant fall even in health conscious individuals. Ensuring adequate fiber intake is important because it helps eliminate waste products via stool, increases satiety and supports a healthy weight, and feeds good gut microbes. By eating a variety of plant foods, you will get adequate amounts of both soluble and insoluble fiber and plenty of colorful polyphenols to boot! A general rule of thumb is to aim for ~10g of fiber per meal. If you are not sure how much fiber you are getting each day, track it to get a rough estimate, then make intentional changes. But wait! If you have been eating a low fiber diet, tummy rumbles and gas may be more pronounced initially as the bacterial composition and stool viscosity changes. Therefore, to avoid discomfort make sure to gradually increase fiber over time, drink plenty of fluids, and move your body daily to help support proper elimination. Unfortunately, certain types of fibers may exacerbate GI symptoms for some individuals. For example, if you are struggling with diarrhea, you may want to limit your intake of insoluble fiber rich foods until the diarrhea is resolved. Alternatively, if you struggle with constipation, slowly increasing your insoluble fiber intake can be helpful. If you struggle with SIBO you likely need to be careful with some fermentable fibers, to reduce gas and bloating, until SIBO is addressed. In general, a healthy gut thrives off of a variety of plant fibers. Therefore, just because you cannot tolerate one type of fiber right now, doesn't mean you may not be able to tolerate it again in the future. It just means that you need to be mindful of which fibers you can or cannot tolerate. Ideally, work 1:1 with a gut health dietitian to help you navigate dietary and supplemental fibers and address the root cause of your digestive woes. FIBER SUPPLEMENTS When using fiber supplements, you first have to ask yourself why do I need a fiber supplement? Is your diet lacking in fiber, then definitely start here first, gradually increasing fiber rich foods in your diet. If struggle with diarrhea you start by increasing soluble fiber rich foods and reducing insoluble fiber rich foods until loose stools improve. If this doesn't work, then try psyllium or Benefiber for some immediate support. Whereas if you struggle with constipation, you may consider adding in coarse wheat bran or using psyllium husk for relief. Finally, if you have SIBO then you may want to avoid inulin/FOS fiber supplements and try Sunfiber (PHGG). The table above will help guide you towards a fiber supplement that may help address your current needs. Ideally, work with a gut health dietitian to navigate all the other fiber options available and help you select a fiber supplement to fit your unique needs. And remember, if your symptoms worsen on a fiber supplement, please stop taking it, and ask your dietitian how to proceed. For some fiber rich recipes check out the links below: Turmeric Quinoa Porridge Festive Massaged Kale Salad Hearty Curry Vegetable Soup Whole Grain Harvest Cornbread Lemon Curry Four Bean Salad Mediterranean Hummus FeedMe Belly Bowl Apple Banana Breakfast Muffins Chickpea Skillet Flatbread References: 1. https://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/0718p11.shtml 2. https://jandonline.org/article/S2212-2672(16)31187-X/fulltext 3. https://jandonline.org/article/S2212-2672(15)01386-6/fulltext 4. Gropper and Smith. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism, 6th Edition. 5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6124841/ 6.https://www.nutricialearningcenter.com/globalassets/pdfs/specialized-adult-nutrition/webinar-slides_fiberprebiotics_adult-health.pdf?epieditmode=False 7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4415970/ |

AuthorLike to read? Then get your evidence based nutrition information here! All posts written by Selva Wohlgemuth, MS, RDN Functional Nutritionist & Clinical Dietitian Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

Providing custom functional nutrition therapy since 2015.

Follow HBN on Social Media!

©Happy Belly Nutrition, LLC 2015-2023

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed